[home]

[Programs]

[Gallery]

[News]

|

The Chicago Public Art Group

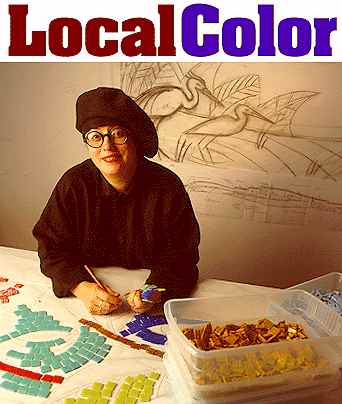

Local Color

The University of Chicago Magazine June 1996

Brightening Chicago's streets and schools, the murals and mosaics of

Olivia Gude and friends address social divisions--and unite communities.

By Kimberly Sweet

Photography by Matthew Gilson

When Olivia Gude read about the racial tension-manifested in fights

and graffiti-brewing at Chicago's Charles Steinmetz High School in spring

1993, she got more than a little upset. She didn't form a committee to

discuss the problems, and she didn't write a letter to protest them, but she

definitely couldn't ignore them. What that school needed, thought Gude,

MFA'82, was a mosaic.

So she approached the principal with her portfolio and her idea: to have

Steinmetz students work together under her supervision to design and create

a multiracially themed piece for the school. The principal gave Gude the

go-ahead, and after two years, with the help of more than 100 students,

Steinmetz High's foyer had 18 sections of mosaic covering over 200 square

feet. And at five hours of work per one square foot of mural, the students

had plenty of time to talk over their differences.

A community muralist and 13-year member of Chicago Public Art Group (CPAG),

Gude sees art not only as a way to beautify the world but also as an agent

of social change, a means to reclaim public space and bring people together.

Fifty or so pieces that Gude has worked on are scattered throughout

Chicago-area streets and schools. If you've been in Hyde Park sometime this

decade, you've probably seen either the mural on the 56th Street Metra

underpass, featuring strikingly real portraits of commuters and their

musings on life, or the brightly hued nature scenes gracing the game room at

International House. Other works adorn a freeway wall in Los Angeles and a

bus in Russia. Her painted murals and tiled mosaics-created in collaboration

with other CPAG artists and community members-address themes of race, class,

gender, place, and justice. For Gude (pronounced "goody"), it's about

fostering "communities of discourse"-physical and intellectual spaces in

which to discuss divisive issues and perhaps close some gaps.

"What's so interesting"-many of her sentences begin this way-"is the way

these murals work. It's the interaction that happens that makes the piece.

What does it mean to have black people and white people sit down and talk

about issues of community?" asks Gude, putting the question on the table

with a quick motion of her hands-three rings on the left one, two rings on

the right. "For communities to function, they have to be constantly kept up.

There has to be this kind of constant interaction."

After majoring in art at Webster College (now University), she began her

career in 1973 as a St. Louis high-school art instructor, viewing teaching

as "a liberating activity that could change people's perceptions." Two years

later, Gude moved to Chicago and started teaching at Bloom Trail High School

in Chicago Heights. There, students changed her own perceptions, as their

interest in painting impelled her to start working in that medium. Most of

her prior art-influenced by the women's movement-had involved patterns,

fabric, sewing, and assemblage. At Bloom Trail, she also painted her first

public pieces: In an effort to keep spring fever at bay, she and fellow art

teacher Jon Pounds-her husband since 1986 and the current head of

CPAG-enlisted their students in end-of-the-school-year mural projects.

But it was when she took two years out to attend the U of C and concentrate

on her own work, explains Gude, intense behind round, black-framed glasses,

that she "really recognized that art, far from being this preserve that was

separate from life, was intrinsically part of all of these issues about

culture, about human possibility, about justice." Coming from a large,

working-class family in St. Louis, she strongly felt that art, even "of the

highest complexity," didn't have to address an elite audience or exist only

in museums and galleries. Gude, along with Pounds, acted on that belief by

doing street pieces-without permission, but using temporary materials such

as chalk-around their South Side neighborhood of Pullman. The works soon

caught the attention of CPAG, known then as Chicago Mural Group.

The group gave Gude a "second graduate education," this one in the

techniques and philosophy of the community mural tradition, while she taught

part time at Bloom Trail, held residencies in other schools, and lectured at

area art schools and universities, including the U of C. Rooted in the late

1960s, the contemporary mural movement, of which CPAG is a part, emphasizes

a mentoring style of training and the idea of a multicultural America.

CPAG's 30-plus members, some of whom Gude has herself helped to train, span

a range of races and nationalities. The members often collaborate, and Gude

in particular ascribes to the method: She is usually one of two or three

lead artists assisted by a number of volunteers. Gude speaks of the concept

of the collective as "a terrifically important image" in present-day

America, "a society of hyperindividuals."

"It's completely different from a Nietz-schean view that what you really

want is one or two supermen or superwomen who can envision this amazing

possibility," says Gude. She believes that collaborations create works

greater than any one person could make while still allowing for each

artist's individual vision.

Some projects begin with the artistic team suggesting a mural to a

community, then talking to residents and local leaders to drum up support

and volunteers. Both are usually in generous supply, in part because CPAG

makes sure the artistic teams represent each community's racial makeup.

Other times a community approaches a particular artist or CPAG for

assistance. Neighborhood groups and schools cosponsor projects through

fund-raising; CPAG may provide seed money or matching funds and also obtains

the necessary permits.

Community volunteers join artists in group brainstorming sessions and

drawing exercises, with those people who have art experience helping to

realize the others' images. After decisions on what to include are reached

by consensus-not majority rule-the sketches are developed, copied, cut, and

pasted into a collage that serves as a model for the final drawing. Once the

mural's outline has been traced on the wall, still more volunteers and youth

assistants join in the painting.

In the past few years, Gude has delved into variations on the traditionally

painted mural, including mosaics and spray-painted art. Usually placed in

doorways and arches, "mosaics are a way of engaging people as they enter a

space," she said in a CPAG newsletter. "There's a pure physicality of the

materials and a decorativeness to them that's unbelievable, like patchwork

quilts." The time-intensive creation of a mosaic involves laying colored

ceramic or glass tiles onto a full-scale drawing of the mural. Contact paper

holds the tiles in place until they've all been laid down and the mural is

ready to be installed, section by section, with the help of professional

tile-setters. With mosaics, Gude has explored the visual tension between

naturalistic images and the geometry of the repeated tile squares.

The wild colors, dramatic lines, and bold words of Gude's spray-can

collaborations stand in sharp opposition to the mosaics but still fit in

with her goals and interests. "Graffiti artists are not the enemies of the

muralists; they're our natural allies," she says. "We were saying, 'Let's

push the murals into a new aesthetic, and let's take the skill and visual

vitality that these young guys have, and think, what other things beside

your name could you write with that skill?'"

Gude intends to keep pushing her aesthetic boundaries. An assistant

professor of art education and studio art at the University of Illinois at

Chicago since last fall, she admits, chuckling, that worries of losing her

edge occasionally nag at her. It seems to be no great danger: She's now

plotting graffiti mosaics-placing chunks of mosaic, perhaps a glass-tile eye

or hand, at random along walls and underpasses around the city.

"Would that be bizarre?" Gude asks. "To suddenly find a fragment of a mosaic

on the side of a building in an alley or something? Would that be cool?"

Pretty cool, but even more exciting is the chance to educate a new

generation of Chicago art teachers. With Olivia Gude, it's certain to be a

collaborative endeavor.

Walls and Bridges

I Welcome Myself to a New Place

(1988)

Conceived to help bond the primarily African-American Roseland

district and its mostly white neighbor Pullman, this 7,200-square-foot mural

takes its name from a line of poetry written by one of Gude's former

high-school students: "I welcome myself to a new place where all the people

can join on in together."

Conceived to help bond the primarily African-American Roseland

district and its mostly white neighbor Pullman, this 7,200-square-foot mural

takes its name from a line of poetry written by one of Gude's former

high-school students: "I welcome myself to a new place where all the people

can join on in together."

Gude and husband Jon Pounds -- Pullman residents -- teamed with artist Marcus

Akinlana and went door-to-door asking for support. Over nine months, more

than 100 people from both neighborhoods helped to raise funds and to create

the mural, located at 113th Street and Cottage Grove under the Metra

railroad tracks that divide Roseland from Pullman. The mural features

historical figures from both communities; African, European, and

Native-American craft patterns; Dutch farmers; and a contemporary black

family.

Several years after finishing the project, while working on the Hyde Park

mural (above), Gude was approached by a young man from Roseland, who,

unaware of her involvement, related the making of the Roseland-Pullman

mural. "That was such a great gift, to have that story come back to me," she

says. "Instead of this child growing up with only an image of neighborhood

segregation, he has a very powerful image of the possibility of cross-racial

cooperation."

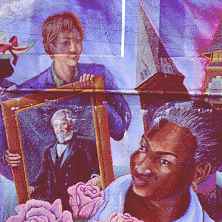

A Place in Time

Where We Come From... Where We're Going

(1992)

In the spring of 1991, Gude stood outside a Hyde Park train station,

tape recorder in hand, asking each passerby, "Where are you coming from?

Where are you going?" Answers came on literal, spiritual, and emotional

levels as people discussed their families, jobs, cultures, hopes, and fears.

Gude, the lead artist, chose the most telling responses and, assisted by

Rolf Mueller, painted those comments and portraits of many of the speakers

on the underpass.

"This mural is meant to ask, Is a neighborhood a community just because the

people are in the same geographic space?" Gude says. She doesn't try to

answer, letting the words speak for themselves. Text has become increasingly

prominent in Gude's art as she attempts to capture "the poetry of the

streets," or a neighborhood's oral history. With this piece, she not only

set out to reveal a bit of Hyde Park's essence, but also to evoke the city

as a whole. Gude points out the muted "Chicago" colors-unusual for a

mural-adding, "It's also probably one of the few murals you'll ever see

where people are wearing coats."

Fresh Air

The Lowell Centennial Mosaics

(1994)

Made of Venetian glass tesserae (tiles), these mosaics frame two

entryways of James Russell Lowell School, marking the school's 1994

centennial. Two of them cover ground-level windows that were bricked over

for security reasons, a not-uncommon practice in Chicago's public schools.

Made of Venetian glass tesserae (tiles), these mosaics frame two

entryways of James Russell Lowell School, marking the school's 1994

centennial. Two of them cover ground-level windows that were bricked over

for security reasons, a not-uncommon practice in Chicago's public schools.

"We 'opened' the windows," says Gude, referring also to Beatriz Santiago

Muñoz, Juan Chavez, and members of Youth Service Project. She cites a

European tradition of reinventing a space in response to contemporary times,

rather than the American way in which old buildings are either destroyed, or

deemed historic and left untouched. "It's not defacing a historic building,"

she adds, "It's adding something at a level of complexity and beauty that

really is architectural."

In recent years, Gude notes, Chicago Public Art Group has completed several

similar projects with Chicago schools, in conjunction with school reform:

"Physically working with the architecture becomes part of what it means to

have local control of schools... what's going to be taught in the school,

what's going to be imagined in the school, what that school means to the

community."

Life Lessons

Where There Is Discord, Harmony: The Power of Art

(1991)

Painted on the west wall of One Artist Row-a building of art studios

and businesses on East 71st Street-this was the third in a series of murals

created by the South Shore Arts Enterprise. After a brainstorming committee

decided the piece should highlight the building's purpose and reflect the

importance of art in all aspects of culture, lead artists Gude and Marcus

Akinlana, assistant Ivan Watkins, and 11 local teenage apprentices set to

work. Days began with set-up time, followed by a brief meditation,

discussion, or lesson, and a harambee-an African-inspired "coming together"

cheer.

Painted on the west wall of One Artist Row-a building of art studios

and businesses on East 71st Street-this was the third in a series of murals

created by the South Shore Arts Enterprise. After a brainstorming committee

decided the piece should highlight the building's purpose and reflect the

importance of art in all aspects of culture, lead artists Gude and Marcus

Akinlana, assistant Ivan Watkins, and 11 local teenage apprentices set to

work. Days began with set-up time, followed by a brief meditation,

discussion, or lesson, and a harambee-an African-inspired "coming together"

cheer.

The spiral dominating the wall symbolizes the cycle of death and rebirth,

while the tree represents life, knowledge, and creativity.

Artists'

tools mingle with artistic products and spiritual and cultural symbols from

Africa, Europe, Asia, and Mexico. The frames allude to the social conditions

in which art is made and seen. Of the final product, Gude wrote, the mural,

"while following the mural tradition of incorporating pattern and symbols

from the cultures of neighborhood residents, eschewed the tradition of using

human figures and an obvious narrative structure."

The spiral dominating the wall symbolizes the cycle of death and rebirth,

while the tree represents life, knowledge, and creativity.

Artists'

tools mingle with artistic products and spiritual and cultural symbols from

Africa, Europe, Asia, and Mexico. The frames allude to the social conditions

in which art is made and seen. Of the final product, Gude wrote, the mural,

"while following the mural tradition of incorporating pattern and symbols

from the cultures of neighborhood residents, eschewed the tradition of using

human figures and an obvious narrative structure."

[Home]

[Programs]

[Gallery]

[News]

|